This is part two of a three-part series inspired by the question Can a hierarchy ever be ethical in polyamory? As I said in Part 1, I have come to the conclusion that this is the wrong question to ask. To get to the right questions, we need to drill down deeper. Part 1 talked about how we define hierarchy, how hierarchies reflect power dynamics within relationships, and why they’re so hard to talk about. In this instalment, we’re going to look closer at some of those power dynamics.

Influence and Control

Any healthy relationship involves a certain amount of influence. While it’s not a good idea to rest your hopes for a relationship on your partner changing, or to make your partner into a project, good partnerships do change the people in them. You may learn new habits, new skills, new hobbies, new ways of communicating. But you also have to learn to prioritize another person’s happiness as well as your own. That means allowing your partner to influence you: it means paying attention to what your partner’s experience is, what their needs are, and working with them to help them get their needs met, along with yours. It means sometimes not doing something you want to do, and sometimes doing something you don’t really want to do, in order to make the relationship work for both of you. It means give and take.

In a healthy relationship, this give and take is negotiated and consensual. Boundaries are respected, bottom lines are recognized and not pushed. You may have to give up pizza on Friday because you’ve had it three date nights in a row and your partner’s craving Thai, you may have to move to a city that’s not your first choice (or even on your list), you might have to take a lower-paying job to make more time with the kids—you may have to make big sacrifices or small ones. But you won’t have to give up friends, family, economic or emotional security, self-worth, self-expression, or any of the things that are important to making you you. And this influence is reciprocal: your partner listens to you and seeks compromise just as much as you do. You both prioritize each other’s happiness and well-being.

The other side of this coin is control. Control is what happens when the give and take stops being consensual and reciprocal, when you stop respecting a partner’s boundaries, when you make your own happiness and meeting your own needs more important than valuing your partner’s agency. It may involve emotional blackmail tactics like threats, shame, gaslighting, withdrawal of affection or resources, or, in extreme cases, physical or sexual abuse. It’s important to recognize that an ongoing pattern of coercive control is the definition of intimate partner abuse—and those tactics I’m talking about are part the power and control wheel that’s used to pinpoint abusive behaviours. However, these coercive tactics are used all the time in both monogamous and polyamorous relationships without rising to the level of abuse.

In poly relationships, control can also manifest through hierarchical agreements where partners give each other the power to make unilateral decisions over other relationships.

You might ask how such agreements might qualify as control if they’re negotiated. That’s because of who’s missing from the negotiating process: the other affected partners. Usually, in hierarchical agreements, the rules are presented to secondary partners as a take-it-or-leave-it proposition, without an opportunity to shape their creation—either in the beginning, or in the future. (This discussion makes up the bulk of chapter 10 in More Than Two.)

In a poly relationship, intimate influence may affect the choices you make about how you interact with other people. It may mean that you don’t date someone you want to date, or you limit the amount of time you can commit, or you put the brakes on a relationship that’s growing too fast and big…because of the way it might affect your other partners, or because of concerns they have. It might even affect your decision whether to be poly at all.

Or, you might make all those same choices because you have a partner who’s exerting control over your other relationships—whether as part of a negotiated power hierarchy, or as part of a pattern of coercive control.

It can often be difficult to tell the difference between the two from outside a relationship—especially if you’re affected by the choices being made.

Let’s give an example. In her memoir The Husband Swap, Louisa Leontiades describes her metamour, Elena, giving an ultimatum to Louisa’s husband, Gilles, who was also Elena’s boyfriend: It’s her or me. Elena made it clear that she could no longer remain in a relationship with Gilles as long as he was in a relationship with Louisa. I won’t spoil the book by telling you what he chose…or how Elena responded. But while I was working with Louisa on the companion guide to the memoir, Lessons in Love and Life to My Younger Self, the two of us had a discussion about whether Elena’s actions constituted a veto of Louisa.

An outside observer who did not know Elena would in fact not be in a position to say whether her actions were a veto or not. Why? Because the difference comes down to expectation and intent. Elena had every right to set boundaries concerning what kind of a relationship she was willing to be involved in—up to and including who she was willing to be metamours with. But in giving Gilles an ultimatum, was she prepared for the possibility that he might say no—thus leaving her in the position of having to make good on her promise to end her relationship with him? Or was she working from an expectation that he would say yes—thus making the ultimatum dangerous for only Louisa, and not for Elena? What would her response be if Gilles said no? Would she be angry? Consider his choice a betrayal? Use shame and guilt to try to get him to do what she wanted? Or would she accept his decision—and leave the relationship?

An underlying element of all these questions is this: Did Elena feel entitled to have Gilles choose her? Healthy relationships are ones in which we can express our needs and desires, but it’s when we feel entitled to have our partners do what we want that things go off the rails. Entitlement makes us feel like it’s okay to overrule our partners’ agency (and that of their partners). If we’re part of a socially sanctioned couple, this is especially dangerous, because we’ve got lots of societal messages feeding that sense of entitlement. And the most damaging parts of hierarchical setups tend to come about when we enshrine entitlement into our relationship agreements.

Back to the Tower

At this point, I really hope you’ve read Part 1, because we’re going back now to our tower and village.

If you can manage to get away from the tower argument of “hierarchy means unequal distribution of resources” and start discussing the real issues (usually this happens when you stop trying to discuss “hierarchies” and instead get into specific kinds of rules, or arrangements such as vetoes), the new tower argument becomes the question of influence. I want to be able to ask for what I want, express my concerns about my metamours to my partners, tell my partners how their other relationships are affecting me, and so on. This is a relatively easy position to defend, because in healthy relationships, partners can influence each other.

Once the tower of intimate influence is defended, however, we see the village once again reoccupied. The village is things that a person feels entitled to control in their partner’s relationship, or rules and structures that are put in place to ensure that one person’s needs are always favoured in the case of resource conflict.

Tower: I want to be able to tell my partner how I feel about a potential new partner and have them consider my feelings in their decision.

Village: I expect my partner not to get involved with a person I’m not comfortable with them being with.Tower: I want my partner to be available to me during emergencies or when I am struggling emotionally.

Village: I expect my partner to be willing to cancel plans with other partners in order to be with me whenever I’m having a hard time.Tower: I have a lifetime commitment with my partner, and I want to feel like they will make choices that honour that commitment.

Village: I don’t want other partners to express desires for commitment from my partner, because I fear it will undermine their commitment to me.

At the same time, I think a lot of people, when they say “I need hierarchy” (or “I need veto”), are really saying “I’m afraid I won’t be able to influence my partner.” It’s not that they specifically want control: it’s that they want influence, and they either haven’t been taught healthy ways to have or use it (especially in poly situations), or they have only been in crappy relationships in the past where they didn’t have influence—so they don’t know what it feels like.

Now, it is a fact that for most people most of the time (but with many exceptions), longer-established, more committed or more entwined partners are likely to have more influence on a pivot partner than newer, less committed or less entwined partners. And that influence is going to affect what happens in other relationships. Sometimes, it may mean not starting a new relationship, or even ending an existing one—even when no pre-established structures are in place to ensure that certain partners are always favoured, even when there’s no control.

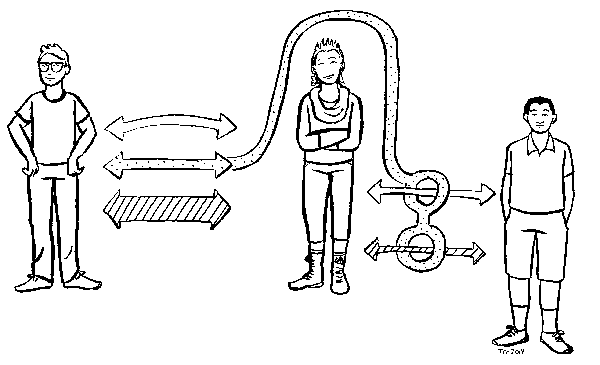

Going back to the diagram from More Than Two that I shared in Part 1:

As explained in the book, the arrow coming from the left and making the circles on the right is power from within the relationship on the left, affecting the level of intensity and commitment in the relationship on the right. But what we don’t really talk about in More Than Two is the fact that the power arrow can come from influence or it can come from control. And if you are the person on the right, your experience of the pivot’s decision may be very much the same regardless.

As a result, as I mentioned in Part 1, in any situation in which there is an unequal distribution of resources—or influence—the person with less may be inclined to look at the situation and say “This is a hierarchy.” And this is where I think the questions of What is a hierarchy? and Are hierarchies ethical? are not the right questions. Because what the person on the right is saying is really “I feel disempowered.” And that matters—and is what we really need to pay attention to.

That will be the subject of Part 3.